From “designer babies” to de-extinct woolly mammoths, recent developments in biotechnology have profoundly changed what we view as possible. But each of these possibilities brings with it its own slew of ethical considerations and anxieties. Is genetic engineering safe? Are we playing God? How far is too far (and will we be able to stop before we get there)?

A new exhibition organized by the NC State University Libraries and the Genetic Engineering and Society Center explores some of these fascinating possibilities and their consequences. Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Futures is on view at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design (on the grounds of NC State University’s campus) through March 15, 2020. Featuring an eclectic ray of works by artists, scientists, designers, and makers of all kinds, the show pushes viewers to take a closer look at biotechnologies through a multitude of creative lenses.

To find out what to expect from the show, Art the Science spoke with curator Hannah Star Rogers about sciart, biotechnology, and more:

What inspired the idea behind Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Future?

My background is in the area of Science and Technology Studies, where I focused on art and science. This exhibition was an opportunity to look particularly at the intersection of biotechnology and art. As these works collectively show, the categories of art and science are determined not by universal axioms or through practices that circumscribe bodies of knowledge.

“The exhibition asks visitors to participate as witnesses, donors, or interlocutors in the nuanced conversations around genetics.”

Hannah Star Rogers

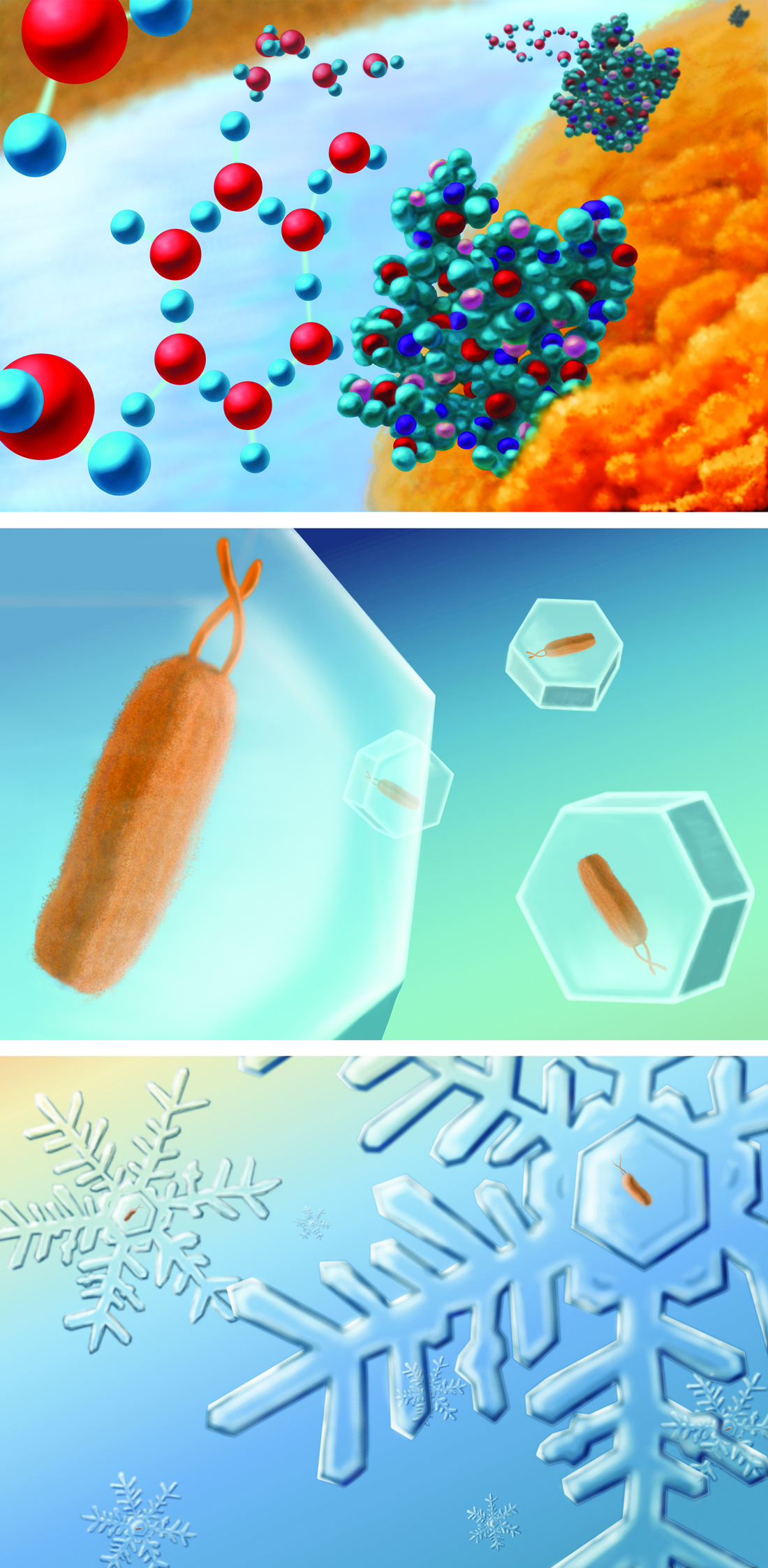

The exhibition asks visitors to participate as witnesses, donors, or interlocutors in the nuanced conversations around genetics. For example, University of Windsor bioart practitioner Jennifer Willet offered new work from her Baroque Biology (Paper Theater) series based on LB Agar petri dishes. These works reposition the object-subject relationship in the context of the history of science through biological vignettes where non-human organisms teach humans complex biotechnological processes within the context of a paper theatre show. This work is in conversation with the use of petri dishes in both bioart and in science, but also with scholarship on the history of science.

Baroque Biology (Paper Theatre) by Jennifer Willet (2019), petri dishes, agar, GMO bacteria, collage materials | Mixed-media collages photographed by Justin Elliott

NC State University is the perfect place to discuss these issues, as the institution has been at the forefront of not only discoveries and innovations in genetics, but is also the home of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center (GES). The Center’s co-director entomologist Fred Gould, along with Molly Renda with NCSU Libraries’ Exhibit Program had discussed creating an art exhibit that addressed the same ethical and practical questions being discussed among GES’s interdisciplinary scholars—including ecologists, social scientists, historians, philosophers, and anthropologists. The Libraries was a natural fit with its record of engaging exhibits, its understanding of the research life cycle, and its access to subject specialists and new technologies. This unique team made it possible to create a multi-site exhibit to engage science, art, and humanist communities.

How did you select the artists? That is, what, specifically, were you looking for in their work?

Our project team, which consisted of interdisciplinary scholars and artists from inside and outside NC State, including Molly Renda, Fred Gould, Todd Kuiken, Elizabeth Pitts, and Patti Mulligan, developed an open call for artists, scientists, designers, and makers at all career stages. This was a very exciting process because we were able to bring together a set of international artists who offered novel ways for our visitors to experience these subjects.

We also invited practitioners who are leaders in this area to participate. In our selection process, we looked for artworks that would engage viewers in examining how genomic sciences could shape the future of our society. We looked for works that question and challenge current biotechnology tropes, as well as projects that embrace the transformative potential of biomedicine.

How do you believe art and design can help raise awareness about genetic engineering, biotechnologies, and their consequences?

In my view these works do more than raise awareness about biotechnology. Rather than simply communicating information about science, they engage the social, political, and aesthetic dimensions of these developments. These, after all, are the areas we need to discuss as a society. Our scientists can tell us the details of the way that CRISPER-Cas9 works—and indeed almost all of the artists in this show worked with scientists to develop these artworks—but we need artists to help us consider what this means and how we want to think about the values these innovations have the potential to support in our society. In this sense, this exhibition is very democratic: it avoids a top down approach to science education by offering a conversation. The artists bring the way they have considered these ideas to the table and ask audiences to think about these issues without suggesting that a technical understanding is the only perspective.

“We need artists to help us consider…how we want to think about the values these innovations have the potential to support in our society.”

Hannah Star Rogers

Your background is in poetry. Does that come through in your curatorial practice?

It’s interesting to think about the way that my interest in poetry and science comes forward when I work with art and science. My sense is that different ways of knowing are always exciting to me, particularly when they are focused on the same subject. As part of the show’s opening we held a symposium which included a variety of people with different backgrounds responding to individual artworks.

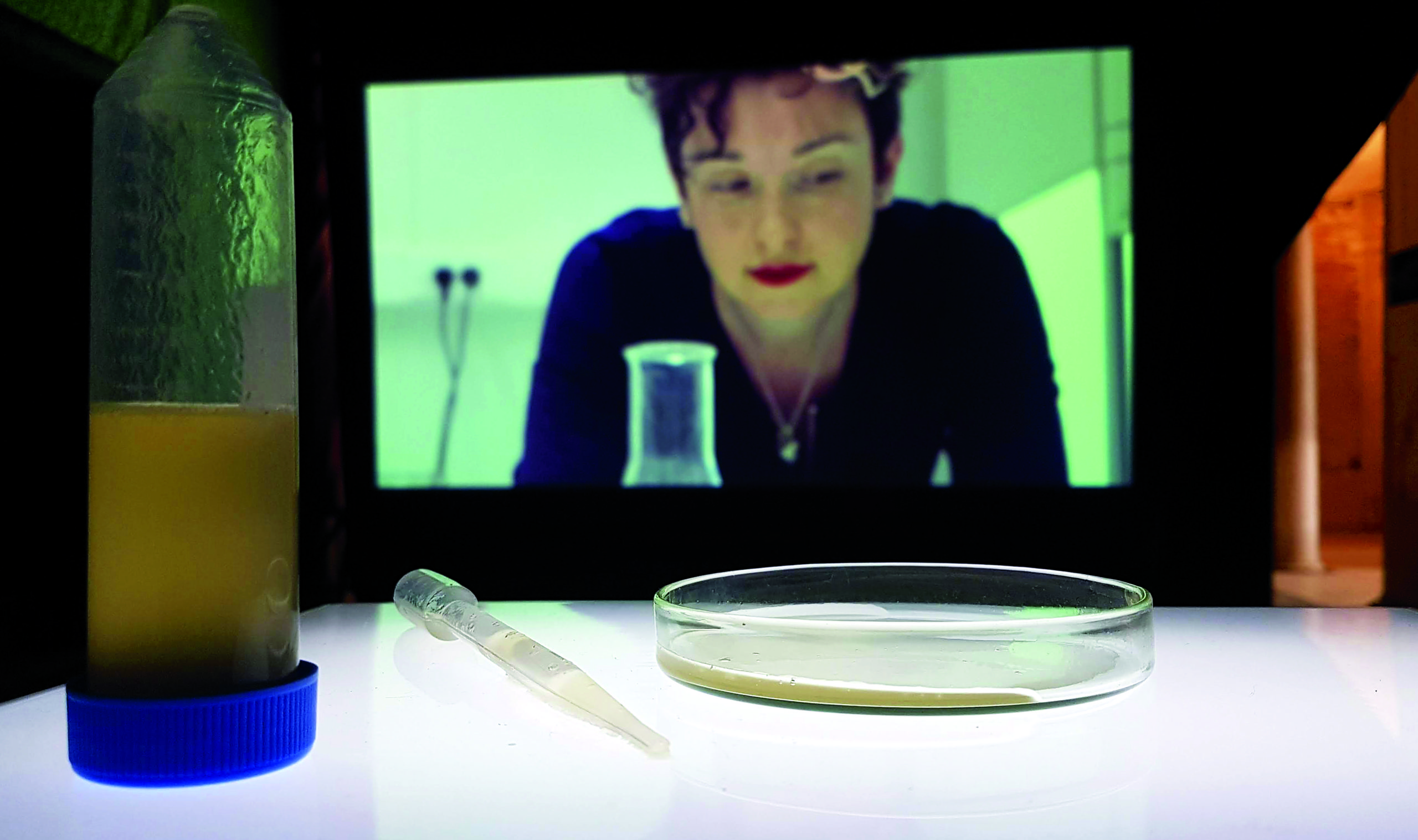

By coincidence, one of these responses was a poem which ekphrastically translated Terra et Venti, a work that considers our ability to geoengineer the earth using synthetic biology’s potential to modify the bacteria P. syringae by Joel Ong, Assistant Professor in Computational Arts at York University. The poem was written by Darrel Stover, cultural historian, science communicator, and performance poet with expertise in Afro-futurism. This response as well as others are available on our website.

As part of the exhibition, From Teosinte to Tomorrow, you planted a 100 x 100-foot corn maze planted at the North Carolina Museum of Art’s museum park. What inspired this work? And how did visitors react to it?

This project was led by Molly Renda, who recruited architect William Dodge, as well as NC State scientists Jim Holland and Bob Patterson to create the piece. It was a wonderful piece of public art which involved many, many volunteers for the care of corn. Student Action with Farmworkers held an event at the maze which brought new perspectives to the piece. The shape of the maze itself was inspired by artist Josef Albers and based on his photographs and drawings during the years he and Anni Albers traveled extensively in Mexico (1930s–60s). The quarter-acre stand of non-GMO tropical field corn was a maze that led to yet more corn: an interior room with a raised bed of teosinte, the wild grass thought to be an ancestor of modern corn. The artists referred to the piece as a time machine because it took visitors back through the physical changes corn has undergone through agriculture.

“I think that is the greatest success a public or community art project can have: unplanned additions that add new dimensions to the conversation.”

Hannah Star Rogers

One highlight was that a community member came by on his bicycle and planted additional vegetable plans around the perimeter of the maze. I think that is the greatest success a public or community art project can have: unplanned additions that add new dimensions to the conversation. Yet another wonderful outcome was that bioart pioneer, Joe Davis, who was featured in the exhibition, had been looking for a field to plow for his own work, Joe Davis Plowed This Field. The piece reflects on his own philosophy of plowing new conceptual fields, and he was able to realize that project in the course of the field remediation.

What other kinds of works will visitors find at Art’s Work?

The projects on view are both analytical and speculative, asking about practices and projecting possibilities for the meanings of art and science in different contexts. This exhibition aims to engage the public about the social uses, familiar and new, that biotechnology might offer through artworks that deal directly with biotechnologies or offer new ways of contextualizing them.

For example, Berlin-based artist and designer Emilia Tikka’s film EUDAMONIA is paired with a speculative injector object which asks whether gene-editing for the purpose of personality change would be positive for individuals and for society. The film shows a philosophical-speculative future scenario where human psyche and character has become a matter of molecular biology and can be altered with a personalized genome editing device. Seeing the mock device in the gallery adds materiality to the speculation.

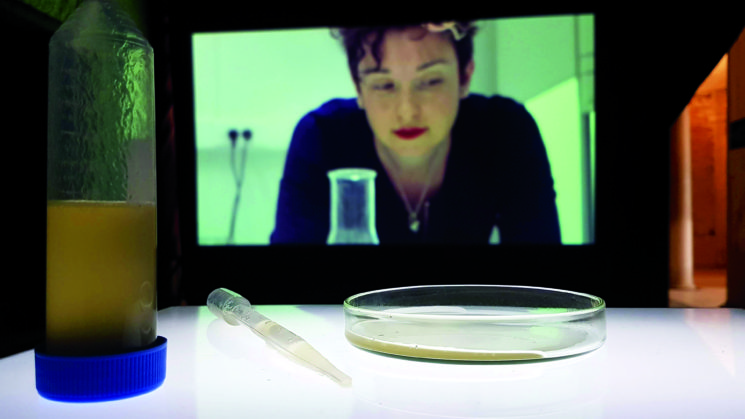

Visitors can also see London-based artist Charlotte Jarvis’ In Posse, which also pairs a physical object and a film. In the gallery, the first iteration of research toward a ‘female sperm’ is displayed on an alter. Beneath that is positioned the artist’s idea of the sacrificed pig associated with the female-only Greek fertility ritual Thesmophoria. Above, in a video reel, we see a collection of blood samples in laboratory settings, which contribute to the research, as well as the artist in the Greek landscape and ocean considering the context outside the laboratory.

What was the most challenging part of putting this exhibition together? What was the most exciting or inspiring?

Working across interdisciplinary lines is both the challenge and joy of this work. These issues are partly about communication and the clarification of goals but they are also about discovering and highlighting the talent from a large pool of contributors. The strengths of artists, designers, librarians, scientists, humanities scholars, museum professionals, and a myriad of volunteers are on display in this exhibition.

Art and science are sometimes thought of as opposite ways of knowing, and sometimes as complementary ones. What do you think?

Funny you should ask, as I am working on a Routledge Handbook on Art, Science, and Technology Studies, forthcoming next year, which looks at precisely this question. This history of art and the history of science have demonstrated that these knowledge communities have changed a great deal over time and, in fact, operate differently in context. For example, what constitutes proof in environmental science, physics, and chemistry are quite different from each other. Similarly, sculpture and performance art have important differences. For me, at the moment, the most interesting way to look at this question is to consider what the labels of art and science do for the public. What values, trust, and degrees of imagination do we offer artists and scientists? How do they position themselves by using these categories to elicit the responses they want from us?

What do you hope Art’s Work leaves viewers with?

I hope this exhibition elicits discussion about genetics in society among our viewers. I hope they are inspired to think about what art and science can do together and in particular to think about their own roles in potential genetic revolutions. The artists in this show are demonstrating that everyone in our society belongs in public conversations about these innovations. Through their works in this exhibition, artists have addressed questions about biotechnology beyond those typical in scientific conversations, including questions of access, sex and gender, race, the rights and roles of animals, and the involvement of corporations. I hope our visitors will be inspired to start conversations of their own.

Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Futures is on view at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design through March 15, 2020. Find out more at the exhibition website or catalogue.