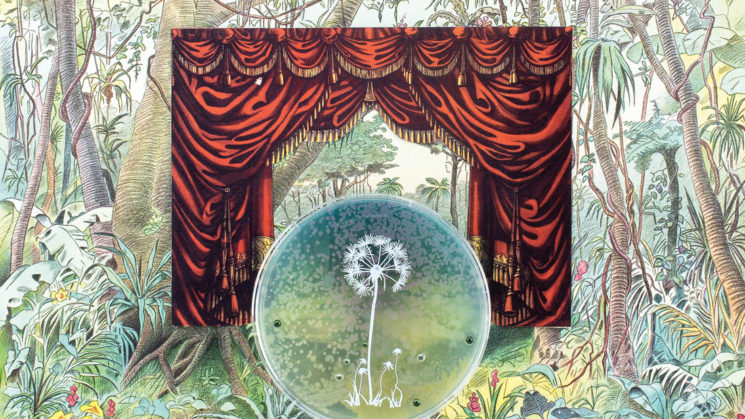

Baroque Biology (Paper Theatre) by Jennifer Willet (2019), petri dishes, agar, GMO bacteria, collage materials | Mixed-media collages photographed by Justin Elliott

This story originally appeared in INDY WEEK, by BRIAN HOWE January 13, 2020

ART’S WORK IN THE AGE OF BIOTECHNOLOGY: SHAPING OUR GENETIC FUTURES

Through Sunday, March 15

The Gregg Museum of Art & Design, Raleigh

Where do we draw the lines dividing art from science, natural from unnatural, and boldness from hubris?

An exhibit at N.C. State’s Gregg Museum of Art & Design doesn’t answer these questions. Instead, it offers head-spinning new ways to ask them at the nexus of art and biotechnology, sharpening our insight into the field’s future and expanding our understanding of it into the past.

These hard-to-classify collaborations between artists and scientists seethe with hot-button issues related to ethics, privacy, human nature, and more. But if they have one message in common, it’s to be careful what you wish for.

Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Futures is the result of more than two years of planning led by Molly Renda, the exhibit program librarian at N.C. State University Libraries, and the university’s Genetic Engineering and Society Center. Guest-curated by Hannah Star Rogers, who studies the intersection of art and science, the main exhibit at the Gregg has annexes in Hill and Hunt libraries.

On a recent tour of the exhibit, Renda and Fred Gould, the co-director of the GESC, said that they wanted to bring artists into the welter of science-and-design innovation taking place at the university because their differing perspectives on fundamental human issues create balance, tension, and discovery.

“In the course of this, I’ve found that artists tend to be more dystopian and designers are more utopian,” Renda says.

“There are different ways of knowing things,” Gould adds. “That’s why Molly came up with the name: not artwork, but art’s work. What is an artist supposed to do?”

Some pieces take on the dangers of day-after-tomorrow DNA testing and engineering technology. Heather Dewey-Hagborg is best known for “Probably Chelsea,” a piece in which she collected DNA samples from Chelsea Manning and generated thirty-two possible portraits of the soldier and activist.

“When we worry about biotechnology, we usually worry that our food is going to be dangerous. But sometimes you wish for something that’s rare: What happens when biotechnology makes it available to you?”

The Gregg is showing a similar piece in which Dewey-Hagborg harvested DNA from cigarette butts and gum she found on the street and created probable—but not definite—replicas of the litterers’ faces, which hang on the walls above the specimens. Dewey-Hagborg demonstrates not only the unnerving extent of what’s currently possible with DNA testing, but also the limits, which create misidentification risks.

Other pieces probe how biotechnology might reshape life as we know it. In a film and a sculpture representing an ancient Greek rite for women, Charlotte Jarvis raises the possibility of creating female sperm, based on the idea that, because stem cells are undifferentiated, you could theoretically teach women’s stem cells to develop into sperm.

Still other pieces pointedly poke holes in the boundary between science and art. Adam Zaretsky’s “Errorarium” (entitled “Bipolar Flowers”) looks like a cross between an arcade cabinet and a terrarium. It houses a few genetically modified Arabidopsis specimens, which Gould calls the “white mice” of research plants. When you turn the knobs, it changes the sonic parameters of a synthesizer, notionally testing the effects of the sound on the mutant plants.

It doesn’t really do anything—or does it? Zaretsky’s experiment with no hypothesis is a playful tweak on science with something a little dangerous in the background.

Joe Davis, a bio-art pioneer, touches on something similar in his piece, which consists of documentation of an experiment where mice roll dice to determine if luck can be bred. Renda says that Davis couldn’t get permission to run the test (universities are wary of drawing attention for ridiculous-seeming experiments), so he did it as conceptual art at N.C. State, instead.

It’s notable that two artists home in on luck, one of many human concepts that genetic engineering, which will allow us to take control of our bodies and environment in untested ways, will transform. In “We Make Our Own Luck Here,” Ciara Redmond has bred four-leaf clovers (without genetic modification), which ruins them—they’re luck’s evidence, not its cause. This whimsical iteration of unconsidered consequences raises a serious question: What else are we not thinking of?

“When we worry about biotechnology, we usually worry that our food is going to be dangerous,” Gould says. “But sometimes you wish for something that’s rare: What happens when biotechnology makes it available to you?”

The exhibit takes an expansive view of biotechnology. Maria McKinney uses semen-extraction straws to sculpt proteins from double-muscled breeding bulls, underscoring that we’ve been tampering with life since long before CRISPR. Biotech feels radically new, but it’s revealed as part of a centuries-long process.

Another part of the exhibit, which closed at the end of October but can still be experienced through virtual reality at the Gregg, was From Teosinte to Tomorrow, Renda’s land-art project at the North Carolina Museum of Art. In what was essentially a walk back through agricultural history, a bed of teosinte, which is thought to be the ancestor of modern maize, waited at the center of a corn maze.

“That teosinte was in some sense genetically enhanced by subsistence farmers in Mexico since the time of the Aztecs,” Gould says. “Now we’re doing it in the laboratory with the same genes—so what’s the difference? Art’s work is to make us think and question.”

Contact arts and culture editor Brian Howe at bhowe@indyweek.com