Dr. Kirsty Wissing’s colloquium presentation highlighted the essential role of Indigenous participation in shaping conservation agendas, advocating for approaches that honor traditional ecological knowledge.

Written by: Jill Furgurson

*Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors as individuals and should not be taken as a reflection of the views of the whole of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center or NC State University.

Image generated with the prompt “Feral cat on Torres Strait islands,” by Adobe, Firefly, 2024

Dr. Kirsty Wissing arose well before 4:00 AM on February 21, 2024, to greet the GES Colloquium community online for her talk: Indigenous Perspectives on Synthetic Biology for Conservation (video, podcast). Dr. Wissing is a Research Fellow at the Australian National University and a Visiting Scientist at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia’s national science agency. Her work considers cross-cultural approaches to environmental disasters such as flooding, invasive species incursions, and biodiversity loss. For those of us tuning in from Raleigh, where it was still midday on February 20, Dr. Wissing brought us into dialogue with the perspectives of Indigenous Torres Strait Islanders’ to consider cultural implications for future island-bound applications of genetic biocontrol technologies such as gene drives.

What is a Land Acknowledgment and why do we recognize the land?

Dr. Wissing began her talk with an acknowledgment of the lands within and surrounding Raleigh as the traditional homelands and gathering places of many Indigenous peoples. She then acknowledged the social and nation groups of Aboriginal Australia and the Indigenous Torres Strait Islanders. According to the Native American and Indigenous Initiatives at Northwestern University, “A Land Acknowledgement is a formal statement that recognizes and respects Indigenous Peoples as traditional stewards of this land and the enduring relationship that exists between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional territories”. The acknowledgment may serve to honor Indigenous people, encourage self-reflection, and motivate further action.

Unsettling conservation futures

To frame her talk, Dr. Wissing reminded us of the incredible toll invasive species (IS) take on ecosystems, noting that IS are an ongoing environmental disaster implemented in over 80 percent of extinctions. She highlighted that current techniques of control often have negative impacts on non-target organisms, whereas new and emerging techniques in synthetic biology, including gene drives, propose to both manage IS at scale and in more targeted, humane ways. As these products move from controlled laboratory settings to field trials, some have promoted islands as “natural laboratories” for gene drive field trial sites. However, islands are also the homes and ancestral lands of many Indigenous peoples. Dr. Wissing asks: How might Indigenous values impact gene drive trials? Are islands “watertight” field sites?

Sassie Island, which has a feral cat population, in the Torres Strait (Zendath Kes). Credit: Wissing 2022

To address these questions, Dr. Wissing referred to the notion of unsettling conservation futures by considering settler-colonial pasts and presents. She referenced Cattelino (2017): ‘Calls for “unsettling nature,” by insisting on the “agency, governance, and scientific participation of indigenous peoples, whose long-term experience with invasive and native species and whose sovereign authority over environmental governance on their territories should inform and delimit” non-Indigenous management practices (p.135).’ The intention behind the idea of ‘unsettling’ is to confront the power dynamics that often occupy environmental governance spaces. Dr. Wissing added that ‘unsettling’ is occurring in science as well as in broader attempts to move beyond ontological (worldview) supremacy, including acknowledging Indigenous insights.

“An application of Indigenous Australian biocultural knowledge and values in synthetic biology”

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia has an Indigenous Science research branch. According to their website, they are “working with Indigenous communities and organisations to create Indigenous-driven science solutions that support sustainable futures for Indigenous peoples, cultures and Country.” This includes a Reconciliation Action Plan and a book on Best Practice Guidelines, as well as a suite of research projects and partnerships. Beginning in January 2021, CSIRO launched a project titled “An application of Indigenous Australian biocultural knowledge and values in synthetic biology”.

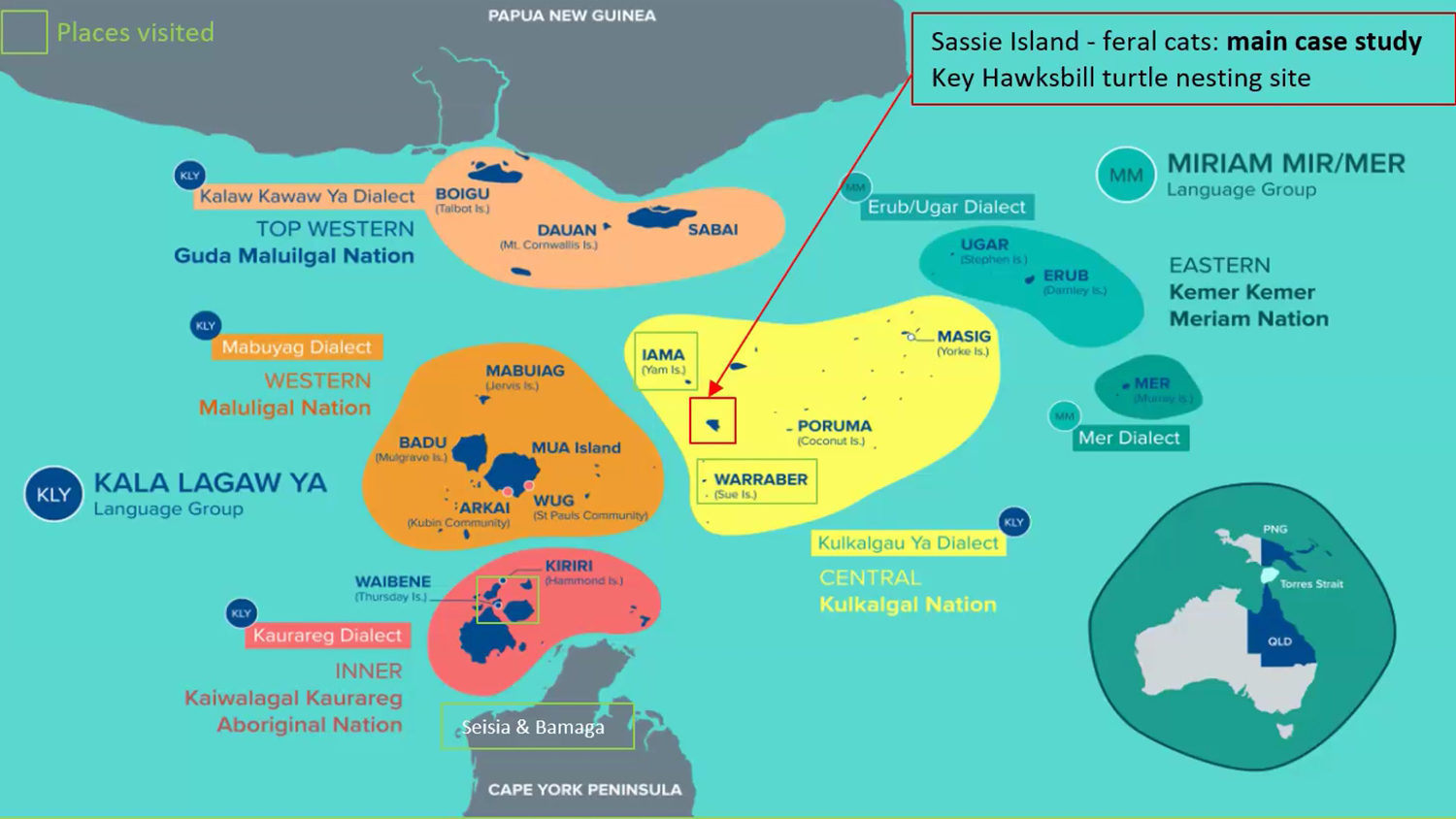

The Torres Strait. Source: Gur A Baradharaw Kod Torres Strait Sea and Land Council’s website (www.gbk.org.au)

Dr. Wissing discussed several aspects of the project, including the selection of the Torres Straight Islands as a site for research. She noted that the Native title determinations, which are federally designated under the Native Title Act to address Native peoples’ titled rights, were strong in these locations. As islands, they represent a special case of pest management and a potential field site for gene drives. As part of the project goals and scope, the CSIRO team aimed to identify Indigenous leaders and organizations as research partners. Sassie Island with its feral cat population, was chosen in part to let Indigenous voices guide the project. Gur A Baradharaw Kod (GBK) was a second site.

The project was recently concluded, and Dr. Wissing shared some of the key themes and findings, including concerns about both containment and ‘knock-on’ effects. She highlighted the importance of respecting, protecting, and facilitating Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP), and engaging in the ‘right way’. This right way includes early engagement, a consideration of both tangible and long-term benefits, and remunerating people’s time and knowledge. Dr. Wissing emphasized perspectives on spiritual considerations, including questions about whether gene drive interventions are acceptable. She likened these concerns to similar concerns raised in the GE Chestnut Case (Dilling et al., 2020). She quoted one Traditional Owner with scientific environmental experience who noted how co-existence and co-management practices both complement and interrupt or destroy each other: “The art is to find where the balance is.”

Fostering dialogue

After Dr. Wissing concluded her presentation, she further engaged in discussion with the GES community. The conversations provided additional depth to the widely applicable material and included thoughts and questions from both natural scientists and social scientists. Topics ranged from suggestions for drawing maps of how gene-drive organisms might flow through the environment to the effect of the recent failed referendum for a constitutional amendment for Indigenous people in Australia. There were several questions focused on the co-design process, including what groups of stakeholders and rights holders were involved, the approach to partnership-building, and the potential impact of funding. In her response, Dr. Wissing alluded to a two-stage approach, in which the initial stage focuses on conversations and partnership building over trying to immediately gather data. The second stage emphasizes ethical engagement.

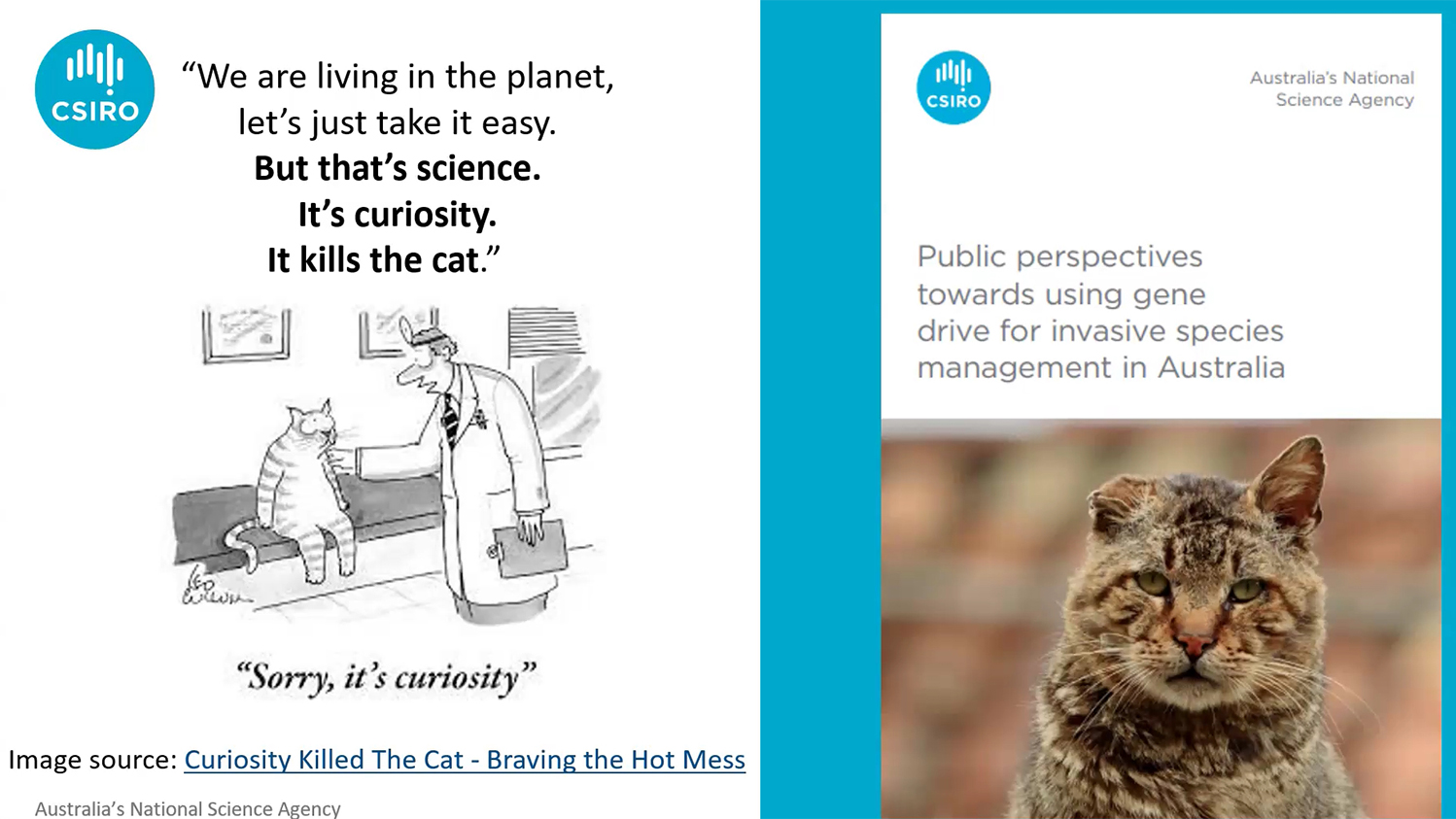

Screenshot from Dr. Wissing’s presentation

Referring back to the discussion of potential benefits for the communities and individuals engaged, a question was asked regarding a “share and care” approach. Dr. Wissing elaborated on the idea of ensuring more immediate benefits to those engaged, especially given that research-related benefits may be years in the future. She noted that this is an important and hard part of early conversations. She addressed conversation fatigue, providing vouchers, making sure information is returned, and the possibility of training Indigenous peoples in monitoring or coming to CSIRO for graduate education. She also gave a nod to the real risk of wasting people’s time, a risk of public engagement in general.

At the heart of Dr. Wissing’s presentation was a recognition of the importance of applying Indigenous values and knowledge to efforts to create sustainable futures. She quoted Hird et al. (2023): “Many scientists working on natural systems do so from a place of love for and connection with the natural world, yet can unknowingly inherit from colonial sciences ways of working that are harmful to Indigenous peoples”. Fortunately, the important ideas and questions posed by Dr. Wissing remain active areas of research within and beyond the GES community. Two recent and relevant colloquia are:

1. Exploring Synergies: Overlapping International Dialogue on Invasive Alien Species Removal on Islands with Synthetic Biology, by Carolina Torres Trueba, Island Conservation (video , podcast)

2. From containment to connectivity: an oceanic approach to gene drive governance, by Riley Taitingfong, Native Nations Institute, University of Arizona (video, podcast)

Kirsty Wissing – Indigenous Perspectives on Synthetic Biology for Conservation | GES Colloquium, 2/20/2024Jill Furgurson is an AgBioFEWS Fellow, STS scholar, and PhD student in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources. Her current research explores how broader engagement can support more inclusive and responsive decision-making around the evaluation of new environmental biotechnologies, such as the genetically engineered (GE) American Chestnut tree. She can be reached at jmfurgur@ncsu.edu.