Written by: Nolan Speicher

*Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors as individuals and should not be taken as a reflection of the views of the whole of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center or NC State University.

In a recent GES colloquium, PhD student Grace Wiedrich shared archival research which invites audiences to reflect on the eugenics movement and its intersections with our local history.

Renowned author Joan Didion once wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Her words echo a strong tradition in communication studies, often referred to as narrative theory, which emphasizes the role that storytelling plays in shaping perceptions of the world. For both Didion and narrative theorists, storytelling is fundamental to what it means to be human. It is less a choice of possible action than it is a condition of our existence.

Among the many stories we tell ourselves today are stories about science. Often, these are tales of social progress, innovation, hope, and even liberation. Consider the many scientific and technological revolutions’ that are said to have existed in the past, or the handful of others that are said to be currently shaping our future. Of course, these are not the only stories that can be told about science. In a recent presentation at the GES Center’s weekly colloquium, Grace Wiedrich, a 3rd year Ph.D. student in NC State’s Communication, Rhetoric, and Digital Media (CRDM), gave the GES community a glimpse into her doctoral work on the 20th-century eugenics movement in the United States.

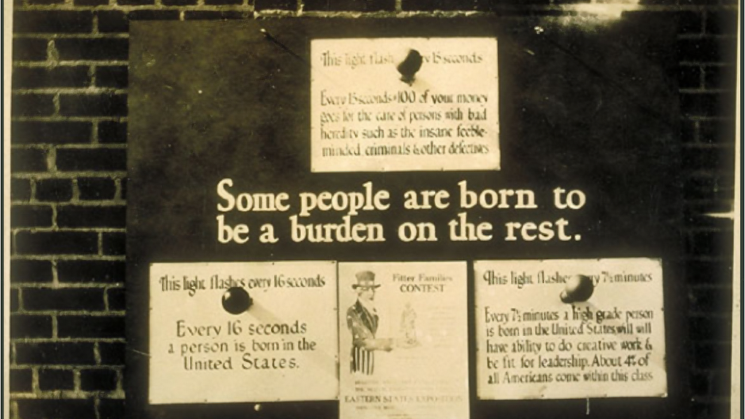

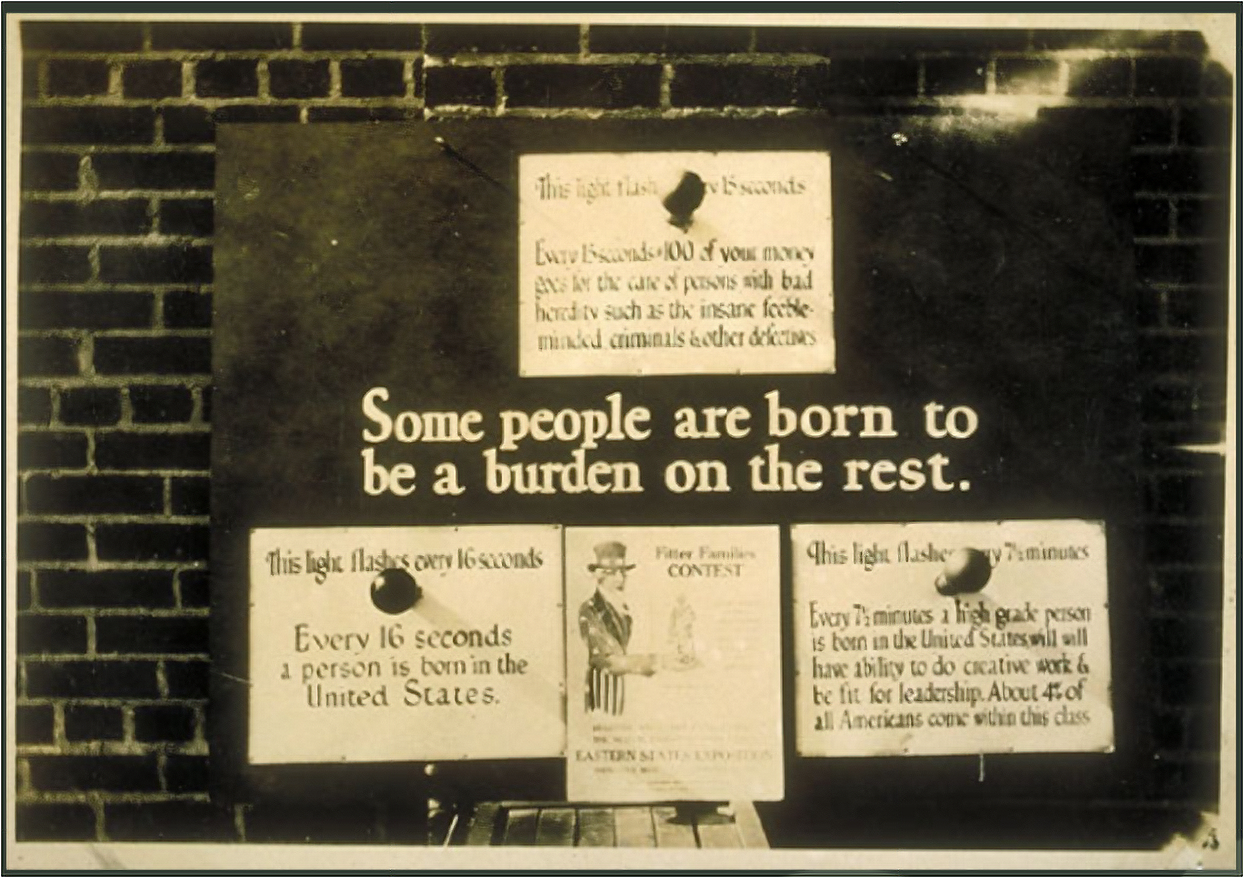

Amidst all the science stories that permeate contemporary academic and popular culture, eugenics tends to be more obscured from public memory. In her colloquium talk (video, podcast), Grace not only reminded us of what the eugenics movement was and how it came to be but also made it “local” in reviewing its manifestations in North Carolina’s political history. This included a reminder of how deeply ingrained the “science” of eugenics became with ordinary socio-political institutions, and how its reach extended far beyond physical attributes to mental characteristics, socioeconomic class, and so-called genetic “predispositions” to criminal behavior. That “better” and more “fit” people could be identified and selected for was an idea that ran its way through contests held at state fairs, educational textbooks, segregated institutions, immigration policy, marriage laws, and forced sterilization of the “defective.” One of the more revealing images from Grace’s presentation is shown below:

This photograph is dated 1926 in the American Eugenics Society Records. The sign at the top reads, “This light flashes every 15 seconds. Every 15 seconds, $1.00 of your money goes for the care of persons with bad heredity such as the insane feebleminded criminals & other defectives”. Below center, promotional material for a “Fitter Families Contest” to be held at the Eastern States Exposition in Springfield, Mass. Source: American Eugenics Society Records

History’s retelling through the written and spoken word is invaluable for grappling with our past, but visual imagery like the photo above can bring the past into close proximity in ways that words cannot. Grace’s use of archival images throughout her presentation gave the GES community a visceral experience of eugenics that was both unsettling and powerful.

A local story

In the latter half of her presentation, Grace continued to bring the eugenics movement even closer as she summarized work that focused more acutely on the state of North Carolina. A key point made here is that North Carolina stands in stark contrast to the popular notion that the U.S. eugenics movement “ended” as a result of WWII. Here we have yet another story, which holds that the science-based eugenics movement existed in the U.S. only until we saw its horrific abuses by the Nazi party in Germany, at which point institutionalized eugenics abruptly ceased. However, in looking closer at this story, we see a far more complex picture. While the eradication of eugenics occurred in some states, others continued and even increased its use. As we learned from Grace’s work, North Carolina is an example of one state that continued the use of eugenics well beyond WWII’s conclusion. The operating arm of the state’s eugenics program was the Eugenics Board of North Carolina (EBNC), which came into being in 1933 and remained in operation until 1977, one of the longest-running of its kind in the U.S. The EBNC oversaw more than 7,500 sterilizations, the majority occurring after WWII and disproportionately affecting African Americans, women, and those of lower socioeconomic class.

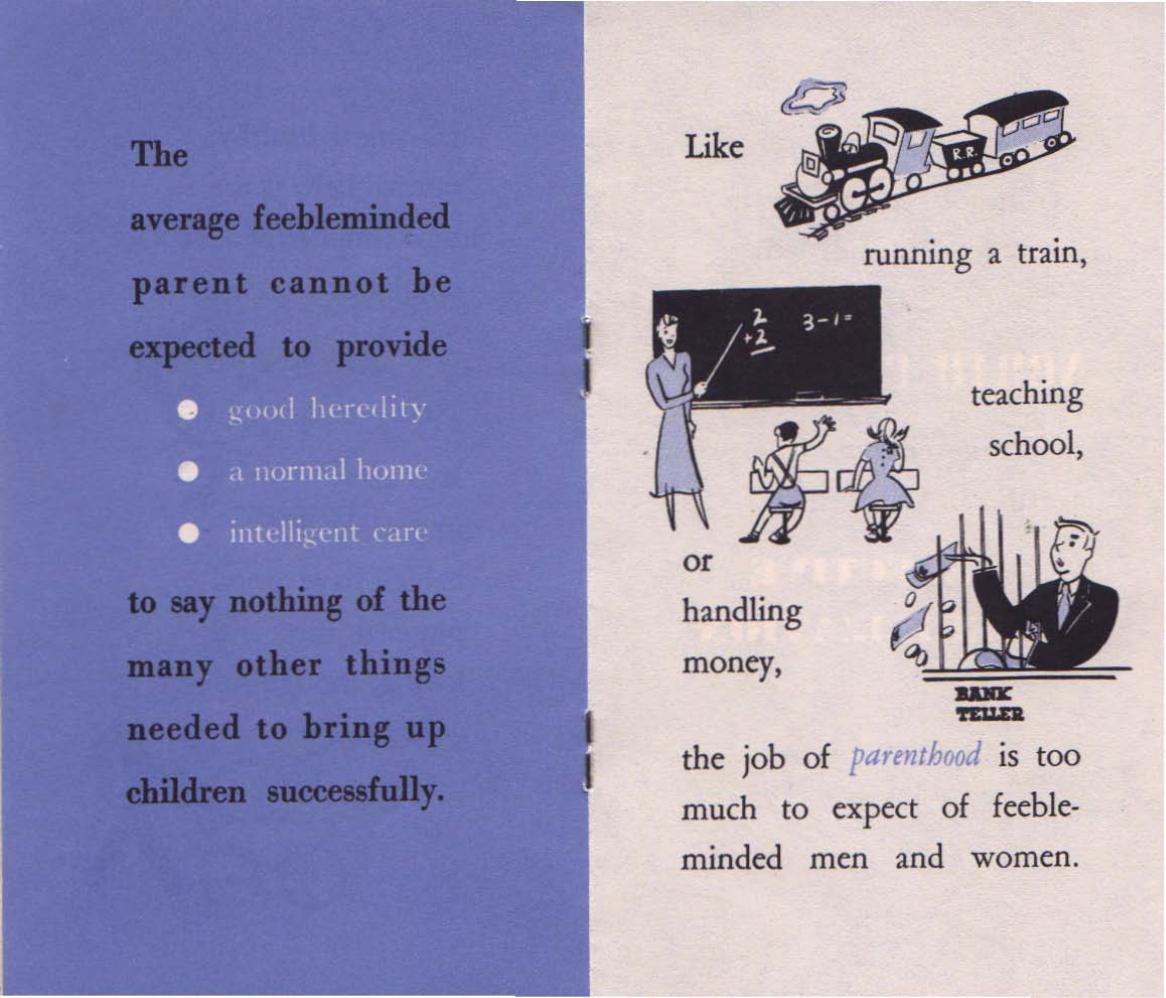

Outside of the EBNC, Grace explained how eugenics found its place in the state’s popular culture through work conducted by the Human Betterment League of North Carolina (HBLNC). This organization, which formed as a subsidiary of California’s Human Betterment Foundation, carried out widespread mail campaigns promoting the use of sterilization programs until the 1970s. Here again, this history was made all the more vivid when Grace shared a prototypical brochure from one such campaign:

A typical campaign artifact used by the Human Betterment League of North Carolina. Source: NC Digital Collections

In discussing these organizations and their activities, Grace’s work illuminates how, particularly in the 1950s, ’60s, and ‘70s, eugenics began intersecting with ongoing social movements in reproductive health care and civil rights. Activists for reproductive rights, for instance, would often raise the issue of elective sterilization as a form of birth control that was necessary at a time when abortion was illegal and contraceptives were inaccessible and unsafe. At the same time, since eugenics ideas and policies disproportionately affected African American communities, their abolition was a prominent goal of the civil rights movement, particularly in southern states.

Inviting reflection and discussion

In closing her presentation, Grace posed questions to the GES community on what this history means for us now and what insights will be gained for the public/political uptake of scientific understandings. The discussion was vibrant and wide-ranging, moving from the use of eugenics rhetoric in contemporary political life to the challenges of doing archival work on this subject. One of the most memorable conversations that took place was on the question of whether the history of eugenics has a place in STEM education. Are educational institutions responsible for introducing this history to future practitioners and innovators? If we aren’t actively doing so, what kinds of future scientists are we molding?

At stake in these questions is whether we, as a scientific community, should tell ourselves this story more routinely and, in more detail, than is currently the case. Surely no scientist is proud of the story, but there may be undesirable consequences to sweeping it under the rug altogether. When we instead choose to remember our past transgressions, we enact our humility, which is integral to constructing and maintaining trust.

Related: Grace Wiedrich – From Plants to People: Mendelian Eugenics in NC in the 20th Century, 1/30/2024

Nolan Speicher is a Ph.D. candidate in Communication, Rhetoric, and Digital Media at NC State and a member of AgBioFEWS cohort 3.