In the annals of history, the American South has been marked by a complex tapestry of culture, tradition, and struggle. Yet, amidst the backdrop of rural landscapes and Jim Crow laws, there lurked a shadowy chapter: the era of eugenics.

From Dr. Krome-Luken’s presentation, “Winner of Large Family Class, Texas State Fair, 1925.” Source: American Philosophical Society

Written by: Ruthie Stokes

*Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors as individuals and should not be taken as a reflection of the views of the whole of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center or NC State University.

In the annals of history, the American South has been marked by a complex tapestry of culture, tradition, and struggle. Yet, amidst the backdrop of rural landscapes and Jim Crow laws, there lurked a shadowy chapter: the era of eugenics.

In the Jim Crow South, laws mandating racial segregation and prohibiting interracial marriage served as manifestations of eugenics ideology. These laws, known as Jim Crow laws, enforced racial segregation in public spaces and institutions, aiming to prevent the mixing of races and preserve the purity of the white race. Embedded in the fabric of society, eugenics found fertile ground in the South, driven by a confluence of factors including racial tensions, agricultural metaphors, and misguided beliefs in Anglo-Saxon superiority.

This blog, written in reflection of a recent GES Colloquium given by Dr. Anna Krome-Lukens – Eugenics and the Welfare State in North Carolina (video), aims to unravel the intricate web of eugenics in the South, tracing its roots and examining how it culminated in the drastic measure of sterilization.

One of the most egregious manifestations of eugenics in the Southern United States was the implementation of “Fitter Family Contests”, such as those held in North Carolina in the early 1900s. These contests, which sought to identify and reward families deemed “fit” based on eugenic criteria, served as a precursor to the widespread practice of sterilization.

In rural areas where the White population was predominant, sterilization became a tool wielded by those in power to maintain racial purity and uphold the tenets of white supremacy. The contests added to the “positive eugenics” expression found in the South through efforts aimed at encouraging the reproduction of individuals perceived as possessing desirable traits, with the goal of strengthening the genetic stock of the White population and promoting social progress. Proponents of positive eugenics sought to cultivate a “better breed” of Southerners through selective breeding and reproductive incentives.

The Appeal of Eugenics

Eugenics Record Office, Field Worker Training Class (Davenport lecturing), circa 1915 at Cold Spring Harbor. Source: eugenicsarchive.org

At the turn of the 20th century, eugenics gained traction in the Southern United States, driven by a desire to advance scientific knowledge and improve societal conditions. Institutions like the Caswell Training School served as bastions of eugenic ideology, advocating for the selective breeding of individuals deemed socially undesirable. The training of eugenics fieldworkers in the mid-1910s, including the notable Sybil Hyatt report of North Carolina, further propelled the eugenics movement forward, legitimizing its principles and practices in the eyes of the public and policymakers alike.

Eugenics Appeal in Agriculture

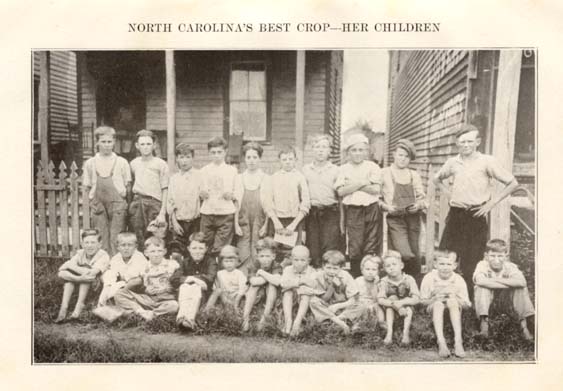

In the predominantly rural areas of the South, where agriculture was the backbone of the economy, eugenicists found fertile ground for their ideas. Drawing upon agricultural metaphors, they likened human beings to crops, arguing for the selective breeding of individuals based on hereditary traits. This distorted analogy reinforced the notion that some individuals were inherently superior to others, perpetuating the myth of racial hierarchy and justifying coercive eugenic measures.

From Dr. Krome-Luken’s presentation, “North Carolina’s Best Crop – Her Children” Source: North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare report, 1920-22

Ideas about Anglo-Saxon Superiority tied to Christianity and Eugenics

Deeply ingrained beliefs in Anglo-Saxon superiority underpinned the eugenics movement in the Southern United States. Racial mixing was viewed as a sign of “feeble-mindedness,” threatening the purity of the white race. Studies such as the Wake Family study, which highlighted the perceived hereditary nature of delinquency, further reinforced eugenicists’ arguments. By framing social issues as genetic flaws, they justified the sterilization of individuals deemed unfit for reproduction, perpetuating systemic discrimination and injustice.

Central to the eugenics movement in the South was a twisted interpretation of Christianity, which posited that humans were responsible for “regenerating” the race. Eugenicists argued that humanity had fallen from its divine perfection and required redemption through selective breeding and the elimination of “inferior” traits. By casting themselves as agents of divine providence, eugenicists portrayed eugenics as a means of restoring the human race to its original glory, free from the taint of degeneracy and moral decay.

At the heart of this convergence lay the belief that humanity was entrusted with the responsibility of “improving” the human race, a duty that eugenicists framed as a divine mandate. Drawing upon religious rhetoric and moral imperatives, eugenicists sought to reconcile their pseudo-scientific beliefs with Christian doctrine, presenting eugenics as a means of fulfilling God’s will and ensuring the prosperity of the chosen people. This belief, no longer rooted in the notion of being made in God’s image, instead framed humans as mere vessels for the propagation of a supposedly superior race. Initially targeted at the poor White population, eugenics proponents sought to “improve” society by controlling reproduction and eliminating those deemed genetically inferior.

The history of eugenics in the Southern United States is a sobering reminder of the dangers of scientific racism and social engineering. Rooted in the desire to advance Southern science and to perpetuate notions of racial superiority, eugenics wrought untold harm upon vulnerable communities, leaving a legacy of trauma and injustice that persists to this day.

As we confront the dark chapters of our past, it is imperative that we recognize the insidious nature of eugenics and work towards a future where all individuals are treated with dignity, respect, and equality, regardless of race or perceived genetic worth.

Speaker’s Blurb

Originally from Virginia, Anna Krome-Lukens completed her Ph.D. in U.S. History at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on the history of social welfare and public health policies, particularly the history of North Carolina’s eugenics and social welfare programs in the early 20th century. Anna is currently working on a book manuscript entitled Reform and Regeneration: Eugenics and the Welfare State in the South, which demonstrates the lasting influence of eugenics in shaping welfare policies and conceptions of citizenship. She directs UNC’s Public Policy Capstone Program and teaches first-year courses on higher education and food policy.

Anna Krome-Lukens – Eugenics and the Welfare State in North Carolina | GES Colloquium, 3/26/2024Ruthie Stokes is a Ph.D. student in Biochemistry in the Alvarez Lab at NC State and is a member of AgBioFEWS cohort 3. She can be reached at rstokes@ncsu.edu.