Recently, on National Agriculture Day, Dr. Jennifer Rowland, the Biotechnology Coordinator at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), gave a talk at the GES Colloquium that left a “big footprint”.

Written by: Christopher J. Gillespie

*Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors as individuals and should not be taken as a reflection of the views of the whole of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center or NC State University.

Have you ever considered the various things you consume every day? The other day, after losing a tennis match to a close friend, I immediately thought, “I should have drunk more water… I should have eaten less junk food…I should have spent less time watching TV the night before”, and so on. This got me thinking about the fact that we humans consume a lot of different things, and it does not just include the things we digest. We consume intangible stuff like media, gossip, and famous movie quotes. We also consume tangible goods like bottles of water or tennis rackets (I did not mean to break it, I swear!). With all that being said, it is safe to say that one of the things we consume the most is biotechnology, which includes products like gas, pharmaceuticals, food, clothing, plastics, and maybe even that tennis racket I mentioned earlier.

Recently, on National Agriculture Day, Dr. Jennifer Rowland, the Biotechnology Coordinator at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), gave a talk at the GES Colloquium that left a “big footprint”. During her 45-minute presentation, Jennifer discussed agricultural biotechnology at USDA and beyond. Dr. Rowland discussed the “USDA’s biotechnology footprint” and highlighted the leadership capacity of the USDA in the agricultural biotechnology space both domestically and globally. Jennifer also spoke about research and development priorities, exportation and cultivation, regulations, and global adoption of agricultural biotechnologies during her talk.

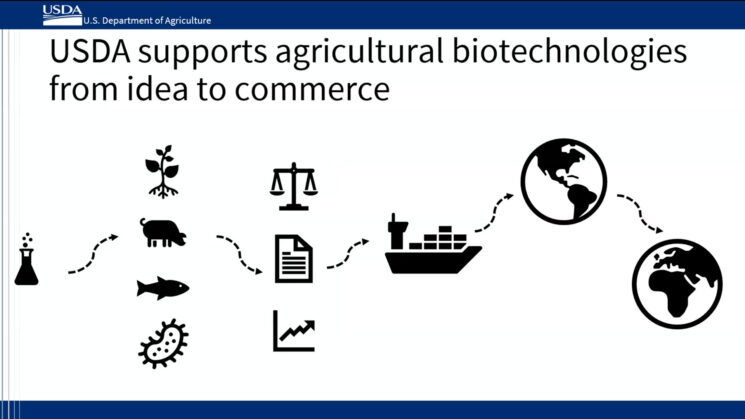

USDA Supports Agricultural Biotechnologies from Idea to Commerce

Slide from Dr. Rowland’s Colloquium presentation illustrating how the USDA supports agricultural biotechnologies from idea to commerce

It is no surprise that USDA has a large biotechnology footprint, considering it is one of the top 10 largest Federal agencies, with over 100,000 employees. “With 100,000 people, it can be tough to find the right person all the time,” said Dr. Rowland, “every week I learn something new [that] the USDA is responsible for.” While this may seem odd, that is exactly the point of her role as a biotechnology coordinator. She serves as an entry point for people who are looking for the right office on a particular biotechnology issue within USDA. While the role is relatively new, as a biotechnology coordinator, Rowland has already increased interagency coordination within the USDA. The USDA has more than 29 agencies throughout the United States and 4,500 offices worldwide. Dr. Rowland works with several agencies with the USDA to support a “whole-of-government approach” to ensure that the benefits of biotechnology are made available to the public at large. The core of this “whole-of-government approach” involves a supporting range of biotechnology activities. Interagency coordination allows the USDA to provide an “innovation to table” framework that covers basic research, applied research, regulation, commercialization, production, labeling (if required), promotion, and trading of biotechnology products. The end goal is to promote a system that ensures that farmers and growers in the United States can benefit from using biotechnology. This means that the USDA supports agricultural biotechnologies from the conception of an idea to the actual commerce of the product.

USDA and Beyond: Questions and Comments from the Audience

Biotech CoverCress image from presentation

After her presentation, Dr. Rowland was asked a few questions and received some comments from the audience. One of the commenters praised the “innovation to table” framework, claiming that in the past, the USDA was “somewhat suspicious of basic research”. They ended their comment by sharing their excitement about the current system that relies on basic research. Dr. Rowland responded by emphasizing the significance of basic research for USDA’s funding, which “eventually leads to new innovations”.

Another audience member asked a question related to the research and development of GE crops that have received funding from the USDA, specifically a crop called “CoverCress”. For background, CoverCress was developed from a wild plant called Pennycress. In the past, Pennycress was initially classified as a weed. However, with a little help from natural evolution and mutagenesis experiments, Pennycress achieved crop status in 2002. Dr. Rowland explained that “CoverCress has been adapted and genome edited for increased oil production,” and “improved cover crop capabilities,” such as overwintering between crop rotations. The research was funded by USDA-NIFA, and a public-private partnership is working to bring it to market. In terms of public benefit, it serves as a cash crop for growers, and it provides soil protection between cropping seasons. “We are really making the most of the land while also protecting it and preserving it,” said Rowland regarding the government investment in this biotechnology. Following a non-food, non-feed exemption year, the CoverCress crop will be made available on the market in 2024.

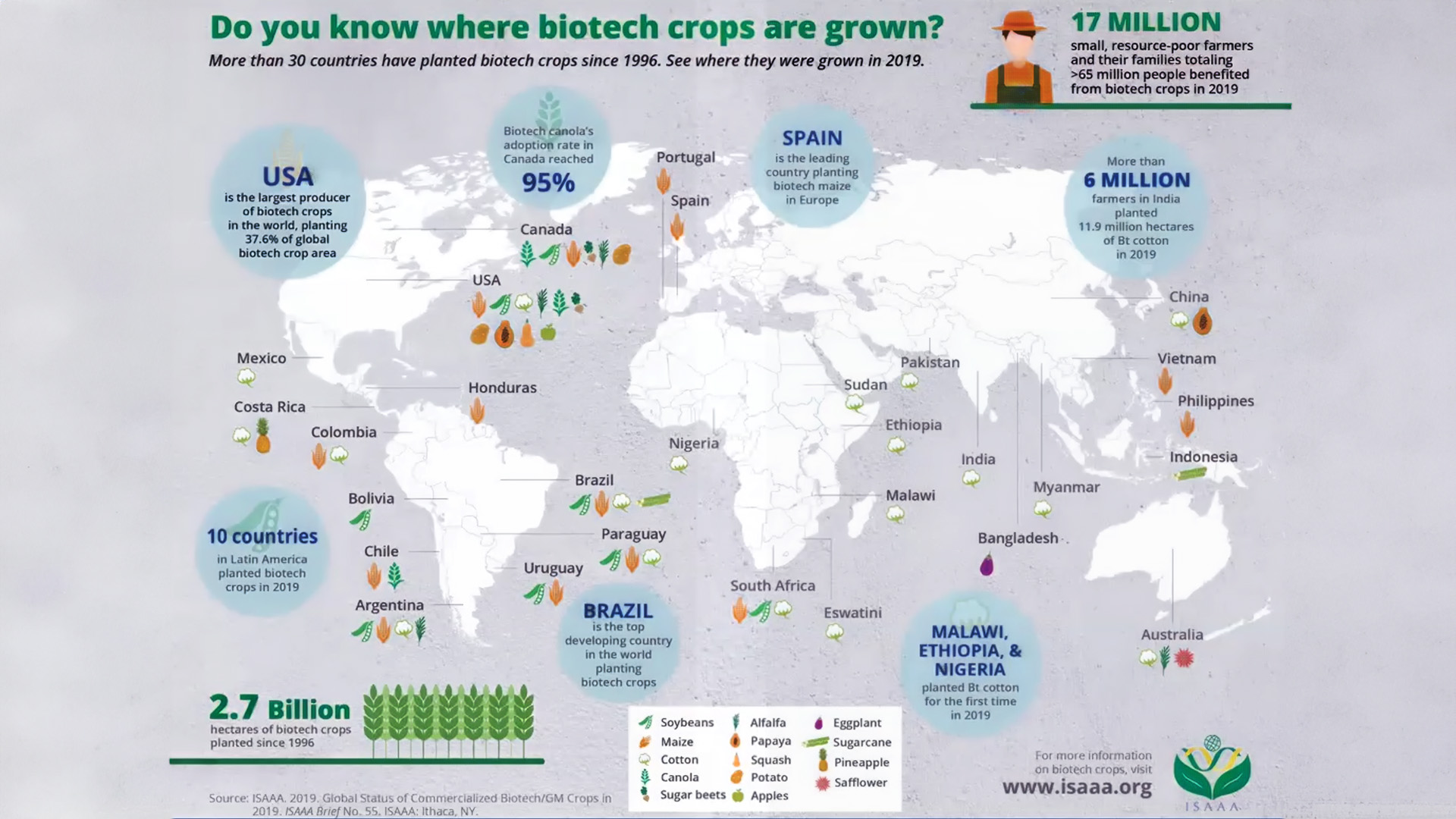

Toward the end of the Q&A, audience members grew curious about the global landscape. When asked about the impact of differing interpretations of gene-edited products on international trade, Dr. Rowland provided her perspective. Dr. Rowland explained that many countries are looking at their current regulations to determine how they can accommodate genome-edited products. “Some countries have determined that using their existing laws, they can make new pathways, and some countries have determined they have to rewrite the laws,” said Rowland. For example, South African regulations require that any biotechnology made in a lab be categorized as a GMO or GE crop.

Source: www.isaaa.org

Meanwhile, the USDA will consider whether or not biotechnology could be achieved through conventional breeding as a standard for this distinction. Dr. Rowland made it clear that while the USDA does consider the global landscape, “We [USDA] have our regulatory authorities, and everything we do has to fit within our existing authorities.” She went on to say, “But we do look at what other people are doing and what support, scientifically and otherwise, they have used to come to that decision.”

A concluding interview with Dr. Jennifer Rowland

A few days after the colloquium, I had the opportunity to briefly interview Dr. Rowland. During the interview, I asked her questions related to her personal life, career, and of course, biotechnology. Dr. Rowland shared that when she is not busy working as a biotechnology coordinator, she enjoys outdoor activities such as running and sightseeing. She also mentioned that she loves trying different cuisines when she travels abroad. When asked about her openness to trying new products, she expressed that she is always eager to try new food biotechnologies. She even joked, saying “I do not even like bananas, but I will definitely try the GE banana when it is released.”

When I asked her to elaborate more on her role as a biotechnology coordinator, she explained that she was initially assigned the role temporarily, before being offered a permanent position. This extra time provided her with an opportunity to adjust to the role and find ways to make the biggest impact. Her goal is to use her position to encourage the development of pathways that promote confidence in new and emerging biotechnologies. Rowland believes that advocates for biotechnology can help create a two-way connection between biotechnology and the public at large by having conversations with their families, friends, and local communities. According to Rowland, it’s crucial for scientists and advocates to share their work with people they have a personal connection with. “Scientists and advocates sharing their work outside of their workspace with people they have a connection with is super critical,” emphasized Rowland, “we do not need to approach these conversations like a thesis defense, it does not need to be confrontational.”

During the last part of the interview, Dr. Rowland and I talked about how the general public can participate in biotechnology regulation. She emphasized the importance of engaging in the public notice and comment period, stating that “for the USDA, receiving public comments is extremely valuable in updating science-based regulation.” Although a rulemaking regarding updates to the bioengineered foods list just passed, another rulemaking on the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard has begun and will continue until June 10, 2024. At the close of our interview, Rowland stated, “I am excited about this position, and I am excited to see where this goes.” As a biotechnology coordinator at the USDA, Dr. Rowland hopes to continue to support innovation and businesses and bring greater variety and greater choice to the American people.

Jen Rowland – Agricultural Biotechnology at USDA and Beyond | GES Colloquium, 3/19/2024Christopher J. Gillespie serves as a Food Supply Chain Impact Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). His role involves providing the federal government with expertise in supply chain management to help strengthen the resilience, diversity, and competitiveness of the U.S. food system. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Crop and Soil Science from Michigan State University, a master’s degree in Plant and Soil Science from Oklahoma State University, and a Ph.D. in Plant Pathology (specializing in Soil Ecology and Biogeochemistry) from North Carolina State University. He can be reached at cjgilles@ncsu.edu.