written By: J. ROYDEN SAAH and ELI D. HORNSTEIN | See Related COLLOQUIUM (4/21/2020) and GES COVID-19 RESOURCES page

*Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors as individuals and should not be taken as a reflection of the views of the whole of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center or NC State University.

Royden Saah:

We are in a global emergency, the scale of which we have not experienced in our lifetimes. Emergency, by definition, is something that poses an immediate survival risk. To counter the COVID-19 pandemic and protect their people from catastrophic loss, governments around the world have implemented public health measures that are rare and may feel extreme in high-income countries. The fact that you are likely reading this blog from home rather than our abandoned workplaces, schools, and public spaces truly frames this crisis.

Royden at pre-deployment training at MSF Ebola Training Centre, Brussels, Belgium 2015

To pull through any emergency, it is critical to pull together. The bigger the emergency, the more important coordination and a unified effort is, and the farther that unity must reach. I know this because I have participated in emerging disease preparations and responses around the world for the past 20 years, including recent Ebola, MERS, and SARS outbreaks.

I now also work on a different type of global plague: the explosion of invasive species causing extinctions on a global scale. The principles of success are similar to a human disease emergency. In our effort to develop powerful biotechnological tools to prevent extinctions, GBIRd (Genetic Biocontrol of Invasive Rodents) has brought together leaders in genetic technology with experts in the social sciences, communication, and biosafety. We want to develop tools that island communities can use to solve the intractable conservation problem of invasive rodents but do so in a safe, and agreeable, manner. In helping to solve the global biodiversity crash, we are skilled in bringing interdisciplinary teams together to solve less immediate, but just as existential problems. Because I have walked in both worlds, I know that teams like mine working on environmental crises are uniquely able to contribute to the COVID-19 health crisis that engulfs us now. This is a call to action for these teams all over the world — pre-existing, agile, highly functional, and used to crisis — to pivot immediately into efforts against the coronavirus.

YES, we need technology development, AND we need social scientists to bring their skills to bear on this problem.

YES, we need stakeholder engagement, AND we need it in a timescale where most experts are not used to functioning.

YES, we need experts pivoting into emergency response, AND we need to be versed and comfortable in our own limitations.

YES, we need to carry-on as best we can with ‘normal’ life, AND we need to stretch and sacrifice and commit more time and energy into collectively understanding and solving the COVID-19 pandemic.

YES, we need to solve the pandemic, AND apply our skills and commitment to other crises that are shaping up to be just as impactful, or worse.

Today is Earth Day. We are facing documented, monumental challenges in biodiversity loss in the near future. Biodiversity loss and climate change are problems that not everyone can ‘feel’ at this time. But like a virus, the pathway to damage is occurring but must not go unaddressed. We are still early in the COVID-19 fight, but my hope is to take the lessons being learned from resolving the pandemic and immediately apply them to the very real, very present conservation problems we are also working to solve.

Eli Hornstein:

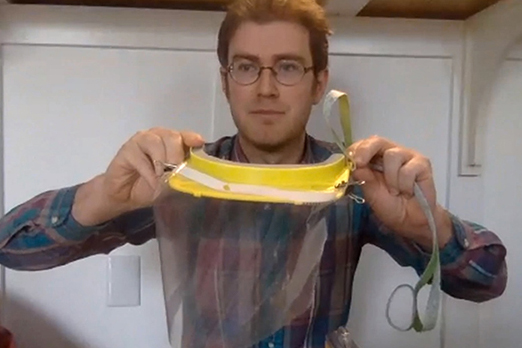

Eli Hornstein shows an example of a 3D printed PPE mask at GES Colloquium

I’m a would-be pivoter. I have no health crisis experience, but I’ve been in conservation and in my day job I’m on an interdisciplinary team and want to contribute. Just as Royden says, I have appreciation for the effort it takes to (a) produce the mindset that supports working nimbly on far-reaching problems, and (b) assemble these experts and get them working together. The weeks-long delays, snarled responses, and contradictions that still slow the coronavirus response are failures to communicate and unify across long distances and differences of view — problems that groups working effectively on other crises have already solved in order to survive. Existing teams that have already done this work in response to other terrible and pressing problems, and their members, are a resource that should not be squandered. We do not want to be squandered.

So far, I have joined a bigger team effort that is manufacturing safety gear in university facilities here at NC State. This work has nothing to do with my technical expertise, but my experience working across fields in other times of urgency and resource limitation allowed me to be useful. I am helping recruit people with home 3D printers to produce simple parts which can be delivered here for safety controls and assembly, sparing the university’s own, more advanced machines for the more difficult work. Hundreds have responded, with businesses and civil society groups close behind them to donate supplies and labor.

Efforts like this are everywhere. On Monday, the social media-based global network Open Source COVID19 Medical Supplies announced that in the four weeks of its existence its members have produced 2,300,000 pieces of protective gear, with production doubling each week. Localized production efforts in some areas now claim to be meeting the entire protective gear requirements of their hospitals. Working within these groups is a flurry of problem-solving. Designs are optimized and re-optimized so quickly in response to feedback that improvements happen almost in real time. A whole ecosystem of technology has been invented in a few months: mask-sewers are working five times as fast with 3D-printed pleating machines, then sending their masks to be tested and sterilized in repurposed research labs and dentist offices. They have their own safety review panels, with medical staff and ‘red teams’ dedicated to predicting problems and allowing designs through–or not. The NIH itself now curates a collection of validated, clinically tested 3D designs for medical equipment. These efforts are encouraging in a special way because the unity and coordination that empowers them are on full display. Let’s have more of that.

All of this is to say nothing of the social and economic sacrifices we are all making, and the technological efforts that dwarf even the miracle that’s been pulled together in our garages and sewing rooms. How about the 76 vaccines in various stages of development? Realize that each of these vaccines is a real, physical entity produced through arduous manipulation at the molecular level–and two months ago none of them existed. How about the unprecedented speed of clinical trials, or the production of ventilators* in a dozen new ways?

The explosion of technological interventions at every level to combat COVID-19 is heartening. Many will not be borne out. Most ideas for homemade ventilators are dead on arrival; vaccine candidates will fail; chloroquine was recently deemed an inappropriate treatment by the NIH. This is oversight and interdisciplinary consideration in real time and it’s essential as described by our GES colleagues. To me it shows the most important “yes and” of all:

YES we can be responsible AND take urgent, unfamiliar action

This is the most important of those points because one day we will pivot back from coronavirus to the next most pressing worldwide emergency, which is the combination of climate change, environmental degradation, and loss of biodiversity, which continue unabated.

In the conservation sphere, technological answers to these problems are often fraught, and put on the back burner in the name of careful consideration. Royden’s organization, GBIRd, is dedicated to carefully figuring out if otherwise insurmountably-invasive mice can be extirpated from islands housing deeply endangered birds, plants, and other species, using gene drive, one of the most cutting-edge, powerful, and therefore worrisome biotechnologies. But discussions about gene drive move at a slow pace, out of fear of doing something bad and a desire to be responsible. I wonder what might happen if we brought the same energy, the same acknowledgement of the responsibility to take action in an emergency, that we have shown in the face of COVID-19 to the way we think about environmental emergencies. Would it change our view of technology, and biotechnology, in conservation?

Just like with the virus, not all of the answers are technological. The personal, economic, and political choices are another huge, “yes and.” But, if reading about the massive efforts to develop and test new technology against the coronavirus emergency gave you hope, consider the following when it comes to the environmental emergency:

- the chance to save the world’s corals from bleaching by accelerating the development of genes for resistance to heat and acid

- re-introduction of the extinct American chestnut to the United States through a disease-resistance gene

- removal of a toxin from cotton seeds to tap a vast, otherwise-wasted supply of protein for humans and animals

And ask, when we pivot back to the environment, if we bring the same energy, optimism, and unity to considering the technological parts of conservation, if you might not see more hope for this emergency as well.