Five Questions with Biotech Policy Expert Jennifer Kuzma

During the past 30 years, the acronym “GMO” has reached the mainstream. You’re likely to hear it in conversation, advertising and, these days, the marketplace.

But what exactly are genetically modified organisms? How are they developed and regulated? How can they be improved and advanced, safely?

These aren’t just questions for biologists and engineers. NC State is home to social scientists and humanists who explore governance, communication, and ethical, historical and societal implications of emerging biotechnologies. Professor Jennifer Kuzma is a leader in this area.

The Goodnight-NCGSK Foundation Distinguished Professor in the School of Public and International Affairs, Kuzma is the co-founder and co-director of NC State’s Genetic Engineering and Society Center.

During the past two decades, she’s contributed more than 150 scholarly publications in the realm of biotechnology regulation and has held positions on numerous national and international committees. In 2018, the American Association for the Advancement of Science named Kuzma an honorary fellow, one of several distinctions she’s earned in her career.

Jennifer Kuzma

What are genetically modified foods? Or GMOs?

- Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are animals, plants or microorganisms that have been modified using modern biotechnology techniques.

- Genetically modified foods (GM foods) are foods derived from GMOs.

GMOs and GM foods can contain foreign genes, or in other words, genes coming from an unrelated species. If the gene you are engineering into a host species comes from an unrelated species, scientists use the term transgenic. If the engineered genes come from related species, scientists use the term cisgenic.

Gene editing is a subset of biotechnology that uses enzymes to cut the genome in a very specific location, in order to change a gene in some way.

For example, analogous to changing a letter in a word, biotechnologists can use enzymes that cut at a specific location and rely on the cell’s own repair system to form a small mutation. To make larger changes, scientists can also introduce an engineered DNA template, and cells will copy that sequence into the site for more substantial genetic “edits” (analogous to introducing a new word or sentence in a paragraph).

CRISPR-Cas9 is a new type of gene editing that makes it easier to introduce small or larger genetic changes into a particular gene in a crop. After the edit is made, the foreign genes can be removed from the plant or animal through standard breeding so that only the edited gene will remain. Thus, not all GMOs contain foreign genes.

What GM foods can be found on the market?

In the first decades of agricultural biotechnology (1990-2010), GM foods mainly involved large commodity crops like soybeans, corn and cotton. The two traits engineered into these crops were typically genes involved in pest resistance or herbicide tolerance.

For example, most pest-resistant GM crops contained genes from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, also known as “Bt.” These genes express proteins that poke holes in insects’ guts and kill them. In other words, the pesticide is built into Bt crops through genetic engineering and therefore, under some conditions, farmers can spray fewer chemical pesticides. Most of these GM crops went to animal feed, cotton, corn and soybean oil or corn or soybean meal.

Today, some whole sweet corn with Bt or herbicide-tolerant genes is on the market for human consumption, as are some viral-resistant papaya and squash. Also on the market is the Arctic Apple, a GM apple that resists browning.

Only a few GM animals have been approved for human consumption by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) — the AquAdvantage salmon that contains a growth hormone for faster growth and a GM GalSafe pig for lower allergenicity and reduced tissue rejection for transplantation.

Scientists mark the advent of gene editing as the second generation of GMOs. Several gene-edited crops have been reviewed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for agricultural planting. The only gene-edited crop reviewed for human consumption by the FDA is a high oleic acid soybean, which has a healthier profile of oil and better food processing characteristics. It’s on the market now.

How can I find info about GM crops in the food supply?

In general, it’s difficult for consumers to find out what GM foods are on the market because they aren’t currently labeled in the U.S. Also, different federal agencies regulate GM crops, and there’s not a one-stop shop for finding information about what’s been approved. And even if a GM crop is approved through regulation, it might not be on the market yet.

Starting in 2022, GM crops with foreign DNA will require labeling in the U.S. to comply with the new National Bioengineered Foods Disclosure Law and Standards. However, the new law excludes GM foods that are cisgenic, or those that don’t contain foreign DNA (like oils derived from transgenic GM crops). Furthermore, the labels will use the term “bioengineered” instead of GM, which might be less familiar to consumers. Biotech policy expert Greg Jaffe and I critiqued these and other requirements in a recent article, asking whether it might cause greater confusion among consumers.

If they choose to, consumers can avoid GM and gene-edited foods by purchasing USDA certified organic foods. Some organizations have also instituted “non-GM” labels like the non-GMO project seal.

Are GM foods safe?

As a broad category, GM foods are neither “safe” or “unsafe,” and the scientific consensus is they need to be reviewed on a case by case basis. We can say, however, that current GM foods on the market have not exhibited increased toxicity or allergenicity and have been screened for equivalent nutritional content.

GM foods on the market have been reviewed through the FDA’s voluntary consultation process. So far, there have been no observed adverse health effects from humans consuming GM foods. It is possible that in the future some GM foods would be developed with changed nutritional makeup or increased toxicity or allergenicity.

What is NC State doing to address genetic engineering and GMOs?

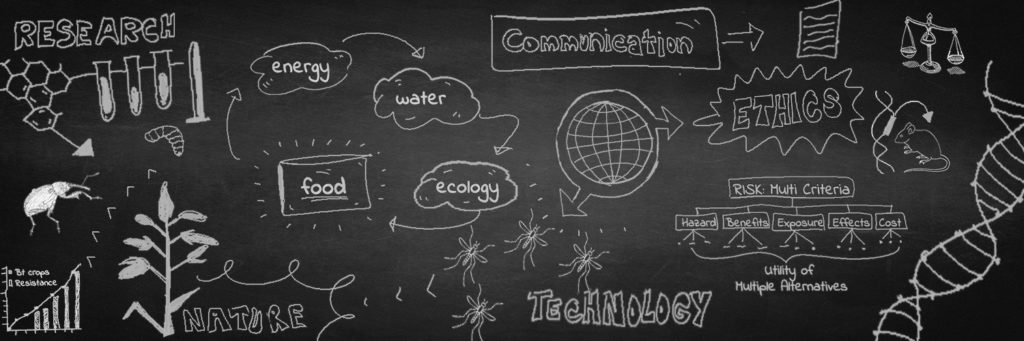

NC State’s Genetic Engineering and Society Center has become an international leader in research, scholarship, education and engagement on the societal implications of genetic engineering and emerging biotechnologies.

The GES center has more than 50 affiliated faculty, houses a graduate minor and several academic courses, and works with nonprofit, governmental, academic and industry partners on projects to consider the broader societal context, science, technology and safety of GMOs.

In addition to the center, NC State sponsors a Genetic Engineering and Society faculty cluster through the Chancellor’s Faculty Excellence Program. This interdisciplinary group of scholars helps hire top faculty and researches cultural, policy and economic aspects of GMOs.

All of this work helps ensure the safe, responsible and equitable development of emerging biotechnologies. This is an increasingly important task, one needed to realize potential benefits to sustainability, ensuring an adequate food supply, reducing illness and disease, and conserving our biodiversity.