NC State’s Jean Ristaino will write a book on her Irish Potato Famine research and work to prevent future plant disease outbreaks while in Dublin as a Fulbright scholar.

February 19, 2024 | 5-min. read

Jean Ristaino stands next to potato plots in the backyard of Down House, Charles Darwin’s home.

Plant pathologist Jean Ristaino took her first international trip to Ireland for events marking the 150th anniversary of the Irish Potato Famine. Nearly 30 years later, the North Carolina State University professor returns to Dublin next month as a Fulbright scholar to share diagnostic tools and expertise about diseases that threaten the food supply.

Ristaino will also work on a book, “The Potato Plague,” about late blight, the disease that caused the famine. Between 1845 and 1852, 1 million Irish people died from starvation and disease, and another 2 million people emigrated from Ireland.

A water mold known as Phytophthora infestans — from “plant destroyer” in Greek — causes late blight in potatoes and tomatoes.

“The disease is still a problem in Ireland, and it still causes global food security issues worldwide,” says Ristaino, William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor of Plant Pathology and founding director of NC State’s Emerging Plant Disease and Global Food Security research cluster.

Ristaino will work with the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine, in Celbridge, Ireland, with plant pathologist Richard O’ Hanlon. With her Irish colleagues, Ristaino will demonstrate a field detection system that she, engineering colleague Qingshan Wei and her research specialist Amanda Saville created, called a LAMP assay — short for loop-mediated isothermal amplification. It allows users to detect P. infestans in 15 to 20 minutes, using a heat block or smartphone rather than expensive diagnostic lab equipment.

Two other distantly related species of Phytophthora threaten Irish trees and native rhododendrons. Ristaino will bring a second LAMP assay developed by graduate student (and GES AgBioFEWS Fellow) Amanda Mainello-Land that can detect these species, P. kernoviae and P. ramorum, as part of efforts to protect Irish farming, food and forestry industries from future threats. Ristaino and Mainello-Land are also studying the genetics of populations of P. ramorum killing Irish larch trees and spreading in nursery plants there.

To keep track of the many species of Phytophthora, Ristaino and her graduate student Allison Coomber, Ph.D., and other colleagues have mapped out a Phytophthora tree of life. Mainello-Land is now creating an expanded living tree specifically for P. ramorum.

“That Phytophthora tree of life tool allows you to quickly identify, with just a few gene sequences, all of the more than 190 different species of Phytophthora,” she explains. “We pulled this data from across labs and countries into this tree-based tool. As people describe new species now, they can query the tree and upload them.”

Origin Story

Ristaino knows Phytophthora infestans at the molecular level, having traced its historical spread through population genomics work. Her research, which included analyzing historical herbarium samples of dried plants, traced the disease’s origin to the South American Andes, where potatoes were first cultivated. Some of those samples were from original outbreaks from the famine found in the Kew Gardens herbarium and at the National Botanic Gardens of Ireland that have been tucked away in collections for centuries.

Ristaino, who is of Scots-Irish ancestry herself on her father’s side, will share some of those disease-detecting adventures in “The Potato Plague” and in lectures for the Society for Irish Plant Pathologists, local universities, natural history associations and the National Botanic Gardens, Glasvenin.

- Jean Ristaino on her first trip to Ireland in 1995 for events marking the 150th anniversary of the Irish Potato Famine.

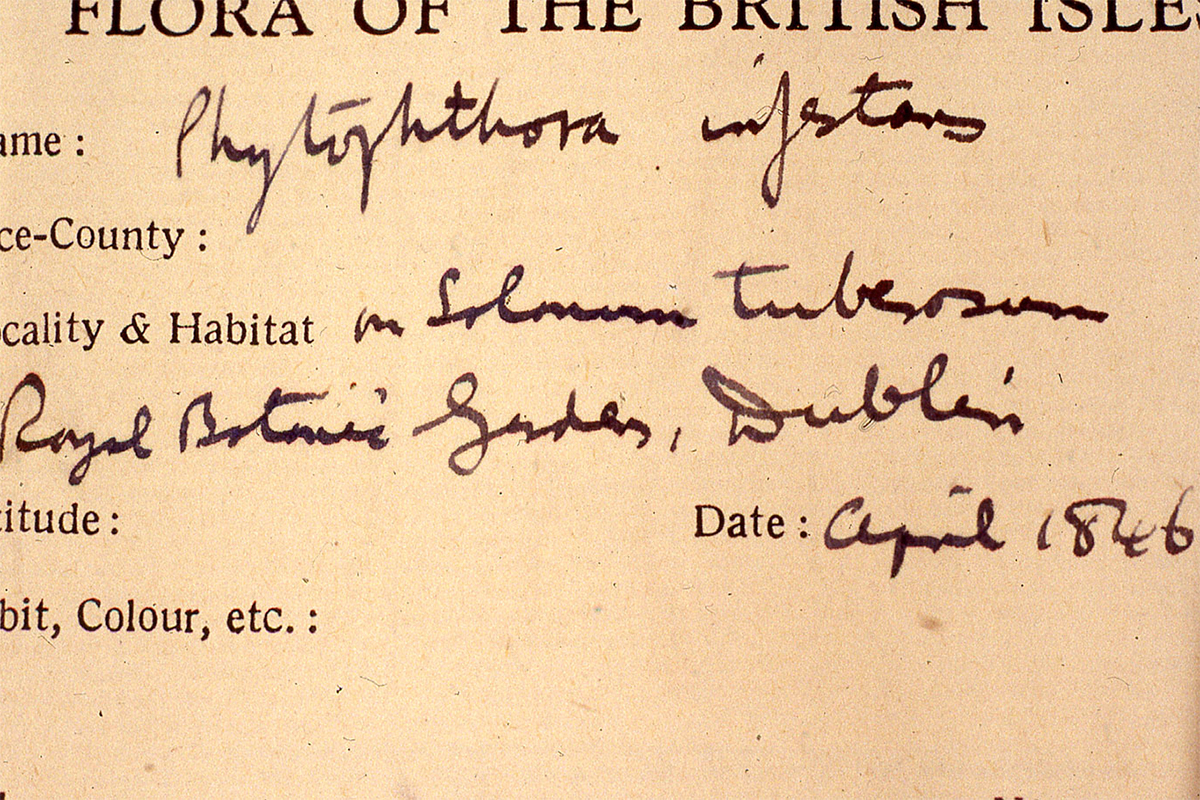

- In 1846, David Moore, a National Botanic Gardens curator during the initial outbreaks of late blight in Ireland, labeled this sample as having Phytophthora infestans. Plant pathologist Jean Ristaino will delve into his historic records this year as a Fulbright scholar.

- Jean Ristaino examines historic plant specimens at the Kew Gardens herbarium in London..

- A North Carolina potato field affected by late blight in 2012.

- Artist Edward Delaney’s Famine Memorial on St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin represents the suffering of the people throughout the Irish Potato Famine.

- Jean Ristaino posed as the “Sherlock of Spuds” for a photo publicizing her research.

“My book is going to be a crime scene investigation study,” she explains. “Who were the victims, the suspects and the many detectives that cracked the potato blight case?”

In search of more insight, she’ll delve into the Irish archival records of early investigator David Moore, a curator at the National Botanic Gardens at Glasnevin during the initial outbreaks of late blight in 1845. Moore experimented with ways of controlling the outbreak. He also tragically lost his wife to famine fever during the pandemic, like so many Irish people.

Though Ristaino is renowned for her work with late blight, the molecular tools she uses can help answer questions about the spread of many other plant diseases.

“We’ve been doing a lot of team science in the last eight to 10 years,” she says. “We have a great team at NC State of people doing genomic surveillance, forecasting, diagnostics and plant disease detection.” In fact, the team was funded by the National Science Foundation with an NSF PIPP phase 1 center planning grant and published a commentary on the need for convergence science to mitigate future plant disease outbreaks and protect the global food supply in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

As part of her next chapter, Ristaino and her husband Gary have recently created a graduate student endowment in plant pathology to help fund the next generation of plant disease “crime stoppers” in her home department. She also hopes her research and book will inspire graduate researchers to excel, and she plans to present a copy to each student who is awarded from the endowment. Stay tuned for a book signing.