Seabirds, such as petrels, are endangered by invasive rodents on islands.

North Carolina State University researchers have received funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop and test a system that would reduce populations of invasive mice on islands to help conserve threatened seabird populations.

NC State leads the two-year, $3.2 million award that seeks to maintain and protect ecosystem biodiversity through control of invasive rodents. It is one of several funded under DARPA’s Safe Genes program. The award can be renewed for an additional $3.2 million in funding.

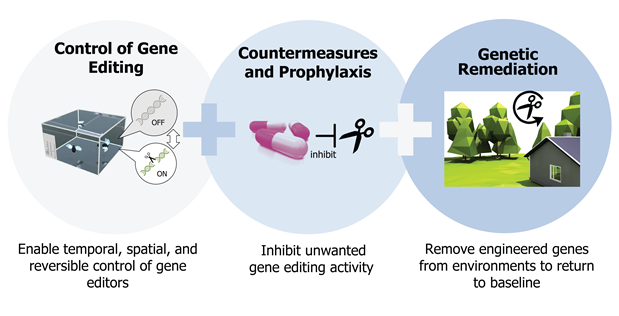

Building the Safe Genes Toolkit

Seven teams aim to develop new knowledge and tools to support responsible innovation in gene editing and protect against threats to genome integrity. (read more) “The field of gene editing has been advancing at an astounding pace, opening the door to previously impossible genetic solutions but without much emphasis on how to mitigate potential downsides,” said Renee Wegrzyn, the Safe Genes program manager. “DARPA launched Safe Genes to begin to refine those capabilities by emphasizing safety first for the full range of potential applications, enabling responsible science to proceed by providing tools to prevent and mitigate misuse.” Source: www.darpa.mil

“The field of gene editing has been advancing at an astounding pace, opening the door to previously impossible genetic solutions but without much emphasis on how to mitigate potential downsides,” said Renee Wegrzyn, the Safe Genes program manager. “DARPA launched Safe Genes to begin to refine those capabilities by emphasizing safety first for the full range of potential applications, enabling responsible science to proceed by providing tools to prevent and mitigate misuse.” Source: www.darpa.mil

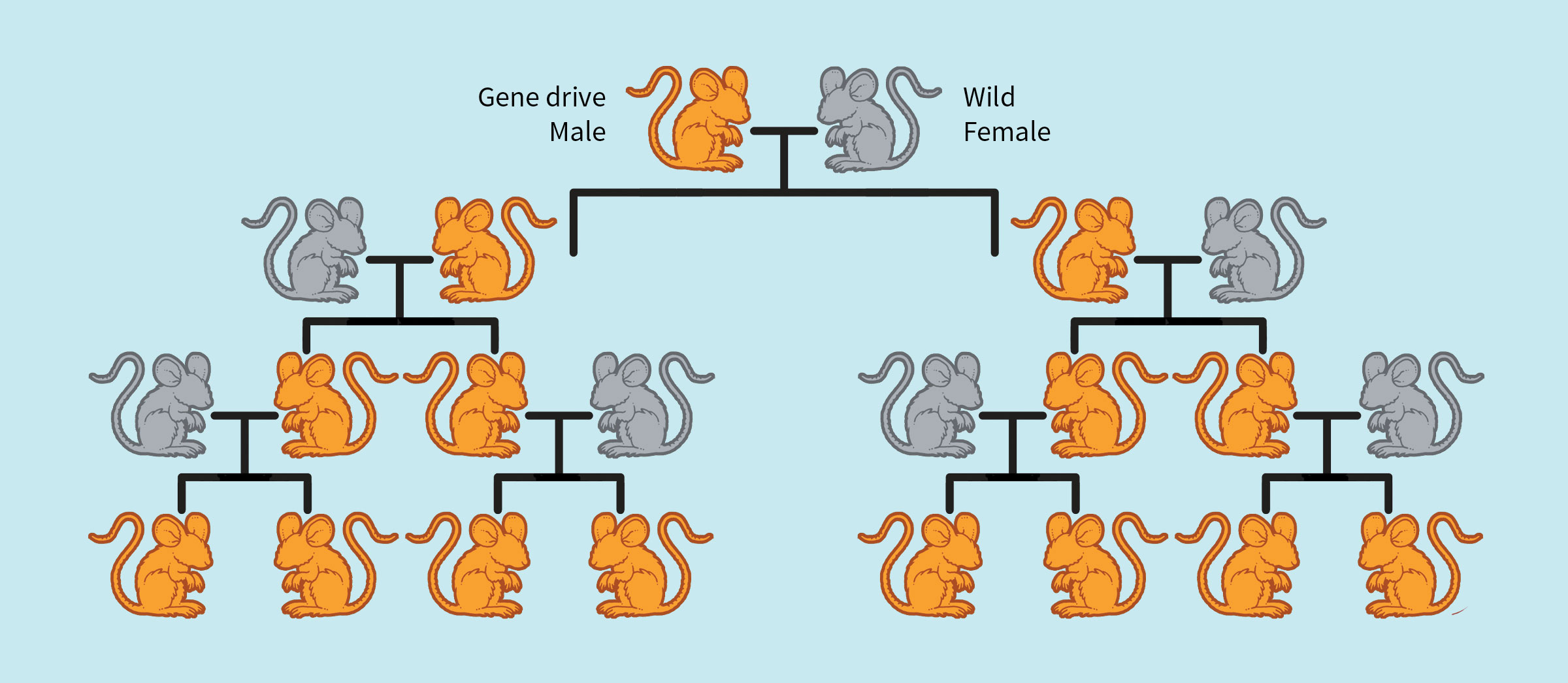

NC State researchers and collaborators will develop and test a gene drive system to lower rodent populations. Gene drive systems work by causing a particular gene or genetic trait to get passed down to a high proportion of offspring from generation to generation.

In one approach, said project principal investigator John Godwin, an NC State professor of biological sciences, researchers would use genetic techniques to affect sex ratios by preventing the development of most female offspring. A few fertile males would continue to drive the sex-change construct through subsequent generations. The lack of females would quickly cause mouse populations to plummet.

How do mice affect seabirds on islands? As an example, Godwin said that large populations of mice on one particular island attracted migrating owls that enjoy feasting on mice. Instead of leaving the island to find food elsewhere, the owls stayed on to exploit this mouse bounty. Once the mouse population was depleted, the owls turned their ravenous appetites to endangered birds called petrels, reducing their already low populations.

“Invasive rodents also prey on native species and destroy sensitive habitats,” Godwin said. “We believe a genetic approach to reduce invasive rodent populations may be necessary, as current approaches, while effective, have their limits. A species-specific approach could do a tremendous amount of good.”

Godwin added that islands are important. They contain less than 5 percent of the earth’s land mass but 20 percent of the world’s species and 40 percent of critically endangered species.

“Islands are hotspots of biological diversity, but they are also hotspots for endangered species,” Godwin said.

How Genetically Modified Mice Could One Day Save Island Birds

THE GOAL: Instead of poisoning invasive mice that devour seabirds on islands, researchers are exploring a powerful new tool, gene drive, to engineer mice that could breed themselves of out existence. One lab, for instance, is building mice that produce only male offspring. The technique is also being studied for combating disease and increasing agricultural yields. It is not out of the lab yet. (read more)

THE GOAL: Instead of poisoning invasive mice that devour seabirds on islands, researchers are exploring a powerful new tool, gene drive, to engineer mice that could breed themselves of out existence. One lab, for instance, is building mice that produce only male offspring. The technique is also being studied for combating disease and increasing agricultural yields. It is not out of the lab yet. (read more)

Source: Audubon.org. Illustration: Eric Nyquist

The project will also develop mathematical models to predict how the gene drive system would function in mice; that effort will be led by NC State mathematical biologist Alun Lloyd, who serves as Drexel Professor of Mathematics. The project will also delve into community engagement and education efforts on gene drive systems, with NC State’s Jason Delborne, an associate professor of forestry and environmental resources, leading that effort.

Godwin stressed the DARPA requirement that testing whether the gene drives developed can reduce mouse numbers will be performed only in highly biosecure, simulated natural environment facilities; no modified mice will be released into the wild or onto any island.

Godwin said that reversibility of the gene drive construct is also an important part of the work.

In the end, Godwin said the Safe Genes program efforts – some of which involve mosquitoes and worms – will “run on parallel tracks aimed at enabling the safe and effective use of promising gene drives.”

NC State will work with academic, nonprofit and government partners on the project, with colleagues from Texas A&M University, the University of Adelaide in Australia, Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), Island Conservation and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Wildlife Research Center involved.

– kulikowski –

Another version of this post was originally published in NC State News.